When I am asked to describe the challenges of being a rabbi for liberal-minded Jews, I would say it consists largely of interpreting our Jewish religion for people who do not think of themselves as particularly religious. You might be surprised to hear me admit this, but I can hardly recall a single instance in which any members ever told me that they actually consider themselves to be religious.

When I am asked to describe the challenges of being a rabbi for liberal-minded Jews, I would say it consists largely of interpreting our Jewish religion for people who do not think of themselves as particularly religious. You might be surprised to hear me admit this, but I can hardly recall a single instance in which any members ever told me that they actually consider themselves to be religious.

Giving sermons on the Jewish religion to people who do not consider themselves religious presents an interesting challenge, especially on the High Holy Days, when everyone shows up. You might wonder: Doesn’t this become a little discouraging for a rabbi? Well sure, I admit it; it does at times. And yet, as the years have gone by, I have come to understand a little better just how Judaism continues to be a strong source of motivation for so many people, despite their apparent lack of religiosity. Some of the best Jews I know, meaning those who most take the meaning of Judaism to heart, hardly ever attend religious services. And this is what keeps me motivated.

People often will tell me that even though they are not religious, still they feel “very Jewish.” This is what I want to discuss with you.

I am sure that for many Jews, when they say they “feel very Jewish” they are alluding to a vague kind of ethnic identification. They may light up when they hear or use the few Yiddish words in their vocabulary, enjoy the usual foods, or tune into favorite programs with Jewish characters. They may feel proud when someone with a Jewish-sounding name accomplishes something notable, and yes, they feel a little ashamed when someone with a Jewish-sounding name is arrested or disgraced. All of these Jewish impulses may be understandable but I’m sorry to say, it really doesn’t amount to a hill of beans.

Feeling Jewish

I am, of course, happy to hear of Jews feeling very Jewish. I should also add that I do realize that one does not actually have to be Jewish to feel Jewish, and that’s fine too. But simply “feeling Jewish” just isn’t sufficient. A feeling is an emotion, and nothing more. There is no requirement for one to act on an emotion. You just feel it. But I must remind you that feeling Jewish, authentically, comes with baggage; with definite ethical expectations that we call mitzvot. Take these away and you are really left with very little, something which might be called “Jewishness,” actually these days it is often referred to as “Jew-ish” but certainly nothing of enduring value.

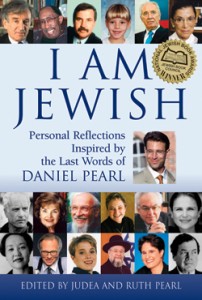

Before the journalist Daniel Pearl was murdered, the terrorists compelled him to make a statement on videotape. His last words were: “I am Jewish.” Some years ago, Daniel’s parents inquired of a wide variety of Jewish individuals what “I am Jewish” means to them, and they assembled a book of the responses, and I would like to read just a few of them to you.

From Larry King: “Now, let’s get this straight: I am not religious. I guess you could say I am agnostic. That is, I don’t know if there is a God or not. But I’m certainly culturally Jewish… Judaism…. is an imprint I carry with me everywhere. I was taught to hate prejudice. I was taught the values of loyalty -the values of family. I was certainly embedded with strong Jewish values of education and learning…”

And writer, producer and social activist Norman Lear wrote: “I identify with everything in life as a Jew. The Jewish contribution over the centuries to literature, art, science, theatre, music, philosophy, the humanities, public policy, and the field of philanthropy awes me and fills me with pride and inspiration. As to Judaism, the religion: I love the congregation but find myself less interested in the ritual… My description [of myself], as I feel it, would be of: total Jew.”

Neither Norman Lear nor Larry King describe themselves as religious Jews. But, it seems to me, both absolutely understand the essence of the Jewish experience. Being Jewish means to see the world through Jewish eyes, and to conduct one’s day-to-day life with a Jewish conscience.

It seems to me that the word “religion” may not be the best way of referring to Judaism. When we say “the Jewish religion” most people think we are talking about rituals and ceremonies. It would be more accurate to describe Judaism as a value system. It is a way of ascribing meaning to our all-too-brief existence, and acknowledging that there are definite ethical principles by which we are to supposed conduct our day-to-day lives.

In the Talmud, in the tractate called Hagigah, we find a most unusual and intriguing statement: It is a declaration attributed to God, which states: “Better that the people of Israel should abandon Me, but follow My commandments.” This is truly remarkable proclamation, perhaps even unique in religious literature. Essentially, it tells us that God actually regards ethical conduct as more important than religious belief. The rabbi with whom I grew up put it this way: “Judaism has more respect for an atheist who acts like a mensch than for a schlemiel who merely believes.”

To be Jewish, I believe, not only means to feel Jewish in one’s heart; it means we’ve got to have a Jewish heart. And if you don’t, you may, of course, call yourself Jewish, but it certainly doesn’t mean very much.

At the core of the Jewish experience is humanitarianism. One simply cannot be a good Jew without having compassion for others. This is the entire point of Judaism. Judaism teaches us that it is our obligation to feel the pain of others and then do whatever we can to be of help, to those who are far, far less well off than we are.

Fr. Michael Fleger, the exceptional priest of St. Sabina’s Catholic Church on the south side, of Chicago, delivered the very best Jewish sermon I ever heard from any pulpit. He said to the congregation: “I grew up in a home where I was taught to fight for that which I believe in.” And he posed the question: So what is worth your fighting for? “Some day,” he said, “each of us will appear before God, and God will ask: ‘Where are your scars?’ Where are your wounds?’ And if you should say ‘I don’t have any.’ Then God will ask: ‘Was there nothing that you witnessed that was worth being wounded for?’”

So much of what we see all around us should hurt us deeply, but it often doesn’t faze us at all because we have become so accustomed to it. But this is our challenge: never to permit ourselves to become so unfazed by the suffering around us that these cause us no pain. As Fr. Fleger reminded us: Every time we drive by the projects, we should not only lock our car doors, we should weep. Every time we see a person eating out of a garbage can, it should make us want to weep. Every time we see a homeless person sleeping on the street, or in an alleyway, we should feel like weeping.

In the Torah, if I were to identify the one person who is the antithesis to the Jews, it would be the Pharaoh. Pharaoh is the Bible’s quintessential callous individual. As each of the plagues brought destruction upon Egypt, we read that Pharaoh’s heart was hardened. That hardened heart is incompatible with Judaism. I don’t care how “very Jewish” someone claims to feel, if he or she can walk virtually blind and deaf by the massive poverty, illiteracy, homelessness and suffering which exists all around us, then I would have to say that that person’s Jewishness is barely skin-deep.

Judaism is very realistic about human nature. Much as we might like to believe otherwise, the rabbis realized that compassion does not come naturally to everyone, perhaps not even to most people. In the Pirké Avot, composed 2000 years ago, they wrote:

“There are four kinds of human beings. The one who says, What is mine is mine and what is yours is yours. That is the ordinary kind…The one who says, What is mine is yours and what is yours is mine is an fool. The one who says, What is mine is yours and what is yours is yours is a saint. And the one who says, What is mine is mine and what is yours is mine is a sinner.”

It is so easy to be cruel—perhaps not actually cruel, but rather dismissive, apathetic, aloof, unsympathetic, unwilling to put oneself in the other’s shoes. There are some people who, thankfully, are compassionate by nature. But there are so many others, who are not so morally gifted.

For that reason, Judaism does not rely on the milk of human kindness. It sets forth standards and expectations that we call mitzvot. Charity is not an option; we call it tzedekah, which means justice, and we must practice tzedekah whether we are feeling generous or not. Compassion is not an option; it is an expectation. Jews are supposed to have a heart, or at the very least, to act as if we do. Respect and consideration for the weaker members of society is our obligation. Fair treatment of the poor, the disadvantaged and yes…the immigrant, documented or not, are demanded of us.

In our major cities with such abundance, where million dollar plus residences are commonplace, where paying $100 plus for a single meal in upscale restaurants happens all the time, where the demand for luxury consumer goods seems insatiable, it is beyond comprehension that hunger, homelessness, and abject poverty should continue to be tolerated. In this nation of boundless blessings, there should be no room for callousness as millions of our fellow Americans continue to be deprived of the basic human necessities, including adequate medical care, and that so many of our children slip through our education system and never really learn to read or write or add a simple column of figures. The Jewish people, who have suffered far more than our share of injustice and persecution in our history, must never permit our hearts to be hardened like Pharoah’s, neither individually nor collectively. No one claiming to be truly Jewish should close his/her eyes and ears to the poverty and suffering that exists all around us.

Why are Jews expected to fast on Yom Kippur? It is not just to cause us to feel more Jewish; rather it is intended to cause us to act more Jewish. Fasting, by itself, is practically of no value. Fasting is efficacious only when it increases our awareness of human misery. Listen to the powerful admoniton of the prophet Isaiah, which is the Haftarah for Yom Kippur:

“Is this the fast I look for? (Isaiah asks sarcastically) A day of self-affliction? Bowing your head like a reed, and covering yourself with sackcloth and ashes? Is this what you call a fast, a day supposedly acceptable to God? This is the fast I truly look for: to unlock the shackles of injustice, to undo the fetters of bondage, to let the oppressed go free and to break every cruel chain…To share your bread with the hungry, and to bring the homeless poor into your house. When you see the naked, to clothe them, and never to hide yourself from your own brothers and sisters.”

Fasting is intended to teach us something about hunger and deprivation. Having fasted for these 24 hours, if nothing has changed, if we are just as callous, just as hard-hearted, as we were before, then the Yom Kippur fast will have been nothing more than a charade. And, I am sorry to say, perhaps it would have been better not to have fasted at all.

Almost all of us have so much to be grateful for. We are so blessed. And almost all of us have so much to offer. We need to be reminded that to be Jewish means to have a Jewish heart. May our sacred days inspire and enable us to act more Jewish: by opening our eyes a little wider, by listening a little more attentively to the many pleas for help, and then by acting whenever and however we can to help make a better life for the countless others whose lives are far, far less blessed than our own.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.